Why You Can’t Afford To Not Buy A Classic Car!

If you like cars, you probably like classic cars. Like looking at them, at least.

But if you’re like most of us, you probably don’t own one – because you’ve probbaly never been able to afford one.

Well, now you can.

At least, if you can afford a new car. Which, arguably, no one can.

New cars have passed several Event Horizons, the first and most obvious being their initial cost. The average price paid for a new car sailed past $35k for the first time last year. This is well-equipped Camry/Accord family car territory.

People routinely spend this much on minivans, pick-ups and crossover SUVs.

And more on modern muscle cars like Camaro, Mustang and Challenger.

Money in that ballpark could also buy you a classic car – a restored one, brought back to better-than-new mechanical and functional condition. Not necessarily an exotic – but a cool car, regardless.

Including a cool old family car. A classic station wagon, for instance. Or how about a grand land yacht from the ’70s? It may not have air bags – a plus in my mind – but it has something better – lots of steel.

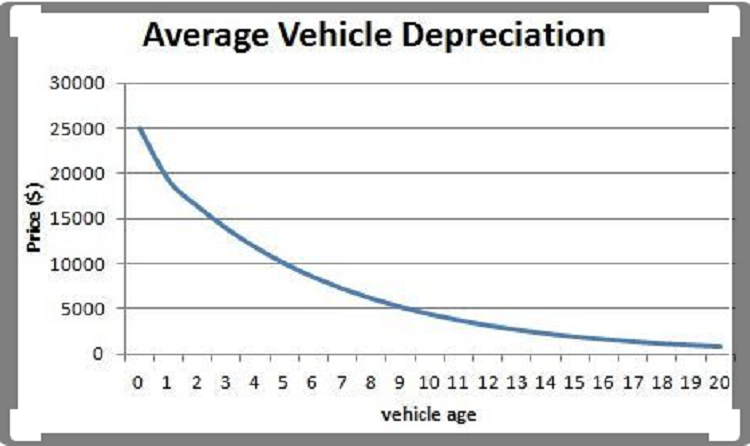

And it’ll be one that won’t be worth a third (or less) what you spent to buy it by the time you finally pay off the loan, as is always the case with new cars.

Which brings us to the second Event Horizon.

Depreciation . . . as opposed to appreciation.

Spend $35k on a new Camry vs. the same sum on restored classic. Gentlemen, start your engines. The relative value of the two will pass each other like cars drag racing in opposite directions. The classic car will very likely be worth more than what you paid for it after five years; the odds of it being worth significantly less are slim.

The odds of your $35k Camry – or any new car – being worth what you paid for it after five years are nonexistent. Even if you put it in hermetically sealed storage and never drove it. After five years, it’d be a five-year-old used car.

It will certainly be worth a bit more than other cars of its make/model/vintage.

But it won’t be worth what you spent.

And to achieve this “savings,” you won’t even have been able to use the thing for its purpose. What point is there in not driving the new car you just bought in order to keep depreciation at bay?

You’re paying to not have transportation.

The third Event Horizon that makes buying a classic car vs. a new car sound financial sense is the economically limited lifespan of new cars – particularly the newest new cars, which are top-heavy with elaborate technology that will inevitably fail and which is often catastrophically expensive to deal with when it does.

This is an economic pratfall most people aren’t aware of.

They are gulled into buying a new car because it is more “reliable” – and because of “lower maintenance costs.” Both being true, but only up to a point. That point arrives when the modern car’s complex systems – especially complex electronic systems – begin to fail.

These can be fixed, of course – almost nothing being unfixable, in principle.

The problem – the Catch 22 – is the cost to fix, in relation to the depreciated value of the car.

Does it make sense to spend $4,000 on a new eight-speed transmission for a depreciated formerly-new car that’s only worth $8,000 – and which will be worth considerably less after another year of depreciation?

And: Do you want to risk spending $4,000 on the aging $8,000 car knowing that another $4,000 bill could drop in your lap tomorrow?

Any new car will remain new in this one not-so-good way – no matter how old it gets. Which is why all new cars are inherently throw-aways. Their value-to-fix ratio becomes untenable after as little as eight years for some luxury cars, which have the most complicated and expensive to fix systems and also depreciate in value much more quickly than average – and is assured for almost any new-ish car after 12 years or so.

Classic cars, on the other hand, can be economically kept going for decades – for a lifetime – because they cost less to repair, including major repairs – and because they appreciate in value the older they get.

Consider, as an example, the case of a classic SUV like the original 1965-’77 Ford Bronco. A survey of current classic car value guides reveals a professionally restored original example can be bought for about $35,000 – which is actually less than what it would cost you to buy a new 4WD SUV with a V8.

If you were to buy the classic Bronco, the money you spent could be called an investment because that classic Bronco – unlike the new one coming out next year – is almost certain to go up rather than down in value. (My own classic car – a 1976 Pontiac Trans-Am – is currently worth at least twice what I paid for it back in 1992, when it was just an old car. That is a pretty decent return on my investment.)

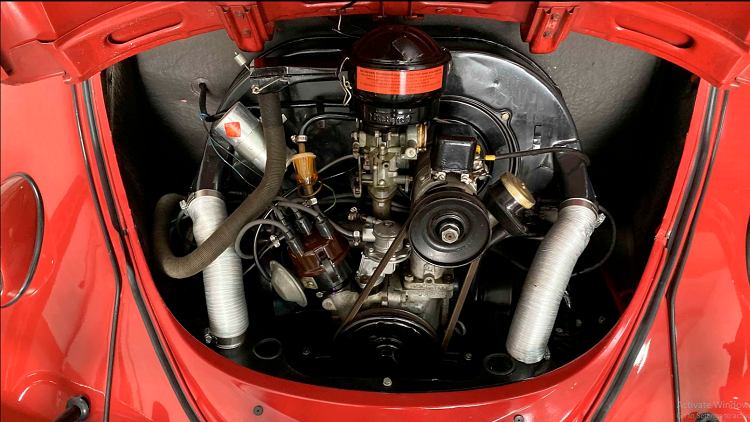

And the classic car’s major systems are all simple – and so relatively inexpensive to repair. As well as repairable – as opposed to replaceable. For example, one can repair – or even rebuild – a classic car’s carburetor, which is the entirety of its fuel delivery system, for less than $100.

As opposed to throwing away the electronic fuel injection parts and replacing them with new parts – of which there are many – and few of them inexpensive.

A classic VW Beetle’s engine takes three quarts of oil; there is no filter. No radiator, either.

There aren’t any computer controls – and no air bags. No Lane Keep Assist, Brake Assist – or ASS to be a pain in yours. Classic cars are Big-Brother-Proof and Nanny-free.

And there’s something else.

You’re exempt from government-mandated “safety” and emissions testing in many states – and eligible for permanent (no annual registration fee to the government) license plates. Technically, you’re only suppose to drive the “antique” to and from car shows and for limited “testing” purposes – not as your everyday driver.

But who’s gonna know?